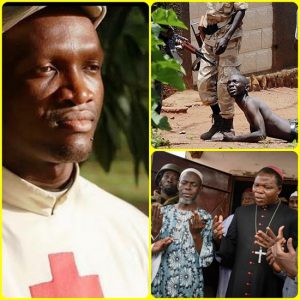

Fr. Bernard Kinvi arrived a few hours ago in Yerevan in Armenia where on Sunday the award ceremony of the #AuroraPrize will take place. Fr. Bernard, together with Marguerite Barankitse, Dr. Tom Catena and Syeda Ghulam Fatima, are among the finalists of the Aurora Prize which every year is awarded to ‘a person or a group of people who have placed their lives at risk to allow other people to survive’.

Fr. Bernard Kinvi arrived a few hours ago in Yerevan in Armenia where on Sunday the award ceremony of the #AuroraPrize will take place. Fr. Bernard, together with Marguerite Barankitse, Dr. Tom Catena and Syeda Ghulam Fatima, are among the finalists of the Aurora Prize which every year is awarded to ‘a person or a group of people who have placed their lives at risk to allow other people to survive’.

For the occasion, we offer you a part of an interview with Fr. Kinvi by Fr. Thomas Rosica for the Salt and Light Catholic Media Foundation. You can find a video of the interview in French HERE

Fr. THOMAS ROSICA: Fr. Kinvi we have been very much moved by the pictures that we have seen and we are honoured to have you here with us here in Toronto today, the day when you will receive an important prize from the organisation Human Rights Watch for your work in Central Africa. Speak to me about your life and your vocation.

Fr. BERNARD KINVI: I was born in Togo into a Christian family, I have three brothers and two sisters and I am the second youngest in the family. I discovered my vocation when my father was about to die after suffering for eighteen years from hemiplegia. I was very close to him during that long period of suffering. I cared for him while he showed me how to pray and how to love God. From that moment onwards I realised that my life would have a meaning only if I gave myself completely to God. The only certain thing is that I did not want to become simply a priest, at least not only that. I wanted to be a priest who knew how to be near to the poor and the sick. I knew a religious community that worked in Lomé. Togo. At Lomé there is a community of the Sisters of Divine Providence, which was founded by St. Luigi Scrosoppi, who serve the poor. After asking these women religious if there was also a male branch of their Institute to which I could consecrate myself, they directed me to Benin to meet the Camillians, a Congregation that worked in the health-care field.

R: Their Founder is St. Camillus de Lellis who had a special vocation to care for the sick and the suffering. What did you discover during your visit to Benin and what did you find in that community?

K: First of all, I discovered that these communities care for the sick. There was an old people’s home. After visiting this old people’s home and reading about the life of St. Camillus, I realised that I would achieve fulfilment if I followed in the footsteps of St. Camillus: a poor man amongst the poor, loving the sick with all one’s heart. St. Camillus saw the sick as his lords, he loved them and he served them following the example of Christ.

R: Then you studied theology in Togo?

K: No, I began to study philosophy in Benin; I did my novitiate in Burkina Faso and then I went back to Benin to finish my four years of theology.

R: You have had a very beautiful experience in Africa, you know a great deal about the situation in these countries which are so dangerous.

K: Certainly!

R: After your degree in theology in 2010, you were ordained a priest. You have been a young priest by now for five years.

K: My first posting was in Central Africa. My Superior asked me if I wanted to go to a country where a new Camillian project was beginning. The community was made up of three priests: three young religious sent on a mission for the first time in Central Africa. I went there without knowing if there was someone there to meet me. When as a parish priest I went to the small village I decided to go wherever there was need.

R: In the Church you found yourself, right in the middle of a major war, in a land divided by an important conflict.

K: Yes, a major conflict which had not yet begun when I began my mission but which began about a year, a year and a half, later. When it began I understood that I ought to move away but at the same time that I had to be amongst the people that I loved and whom I could not abandon. I had an opportunity to flee but there was nowhere that they could go.

R: Why did you stay? Your Superiors, as I have understood matters, gave you an opportunity to leave, is that right?

K: Certainly, but I stayed because I am a Camillian. I chose to serve the sick even if it cost me my life. In reality, when I made this choice I did not understand completely what it meant. But during that period of war when danger was near I understood that I could not abandon the people that I was looking after. Subsequently, when the war had by now begun, I became the director of the hospital which served an area of over 150 kilometres, and therefore I immediately realised that to have closed and abandoned the hospital would have been terrible for the people of that area. I also say that St. Camillus, my Founder, a person I love a great deal, a saint I love a great deal, during the plagues and the wars of the sixteenth century in Italy, where he lived, while people were fleeing from cities infected by the plague…St. Camillus and his companions began their work of care. When people he met asked him “why are you going there, amongst the plague-stricken, you have to escape!”, he replied that it was precisely because of the plague that he had to go there! He took care of people who were plague-stricken even when his friends had already contracted the disease. So I said to myself: now is the time to follow in the footsteps of St. Camillus.

R: One feels that this vocation is in your heart, but it is also true that you also found yourself through your relationship with the Muslim population, above all through the care that you gave them and they received from you. Explain to us what happened in this community, the persecution experienced by the people of this area and their reaction.

K: I often say that we have to be rational, take into consideration, on the one hand, the extremists who do wrong and, on the other, the civilian population with a Muslim majority. They believe in their religion, they are Muslims, and there is nothing wrong in that. As they are a part of the population that can use the services of my hospital, I received them as patients. They have nothing to do with this war. When the war began, there was a group of rebels, most of them Muslims, who had escaped and oppressed people in the name of the Muslims.

R: Were people suffering a lot?

K: Yes! Both religions suffer, both the local religion and the Christian religion. Everyone is persecuted. I myself was threatened by these rebels. They came to my hospital. They broke down the door and wanted my car. They blocked me and aimed a weapon at my head. I entreated them to allow me to live.

They fact that they had wounded me did not preclude me helping the Muslims: they were not involved with these fighters. My concern was to get people into the hospital and the mission. I took in all the wounded and all the Muslims who had been threatened and were in the neighbourhood. I went out to look for them and take them with me to the hospital. I met women, children and many handicapped people who did not have a chance to escape. I moved them and this was life endangering.

There were very many of them, about a hundred people. I remember that I and my religious brother Fr. Patrick used a wheelbarrow to pile up the bodies and we set fire to them so as to assure a decent burial. This was a difficult moment but we had to do this, not because they were Muslims but because they were men, created by God, the breath of God is in them, and God loves them. This is what God asked us to do and this is what we did.

There were very many of them, about a hundred people. I remember that I and my religious brother Fr. Patrick used a wheelbarrow to pile up the bodies and we set fire to them so as to assure a decent burial. This was a difficult moment but we had to do this, not because they were Muslims but because they were men, created by God, the breath of God is in them, and God loves them. This is what God asked us to do and this is what we did.

R: The world is going through a very difficult period. We have just gone through the dramatic events of Paris (November 2015) which were claimed by Islamic extremists whom we cannot see as Muslim faithful. You know them. It is difficult to make a distinction between believers and those who are not. How have you reconciled these two situations?

K: I will only speak about what I know. In the population that I know, I am able to distinguish between who is an extremist and who is not. You recognise the extremists by their weapons, by their threats. We knew who were with the rebels because they threatened people who arrived in the area. I knew the rebels of President Issanabré, who came from another area, he was a fighter who had taken part in many fatal attacks on the non-Muslim population. The majority of these extremists knew each other. The work that I did, I did not do for myself. Many priests of Central Africa did the same thing; the number of priests who welcomed Muslim refugees in their churches and in their parishes is high. Many Christians hid Muslims in their fields and every day in the morning gave them a meal, travelling through the forest for as much as twelve kilometres just to give them food and keep them hidden. This was a sort of common protection. We did not decide to do this but we saw that the situations was grave and that we had to protect the lives of these people.

R: You are not making distinctions. The poor and the suffering have to be helped: who they are and what religion they profess is not important.

K: It does not matter who they are: the rebels also came to the hospital to be treated.

R: And who treated them?

K: When I took care of the rebels, I did not want to know on what side they were, I only saw them as people. I always think that a wish to give love to other people is what is most right. Our presence in this area is very important, a presence that does not make distinctions between people, which maintains a certain neutrality but which at the same time helps everyone. Rules of behaviour are fundamental in this situation; in this way things can be done well.

R: Fr. Bernard, you have used beautiful words: infectious love. This infection also exists in your home. Can I ask you a personal question? You live amidst fear and war. You assist and bury those who die, you take care of the sick. What are the motivations that lead you to do this? You are a young priest, you are thirty-three, you have been forged for sacrifice. I wonder whether you predicted what was in store for you on the day of your ordination. What leads you to go forward?

K: There are, I would say, three things. The first is Jesus Christ, I am crazy about him, I love him. I decided to consecrate my life to him and my life began to have a meaning when I began to do what he did. At the end of his life, Jesus bequeathed to us a single commandment: love one another. Thus we must love everyone as Jesus loves us. Love does not necessarily mean ‘happiness’, but it certainly means loving to the utmost. I do not know what happened. I do not want to know what the future has in store for me. I want to love as Christ taught us: love good people and bad people in an equal way. This is my first motivation. The second is: believe firmly in Christian faith. I am convinced that my life does not end here; I believe that in death we are born again. This  hope in the glory of the soul and the body after death guides me. I also know that even if I die during my work I will live again in Christ. The third motivation is the brothers and sisters with whom I live. I have a brother, Fr. Brice Patrique, an Augustinian father, the Carmelite religious who are with us in the mission and do extraordinary work in the most prudent way. The community of Christian brothers and sisters who are there. We help each other, we speak to each other and we encourage each other. We know that the other priests in the other parishes are fighting for the same cause, that is say to establish justice and peace through reconciliation. This is the motivation that encourages us, spurs us on, and leads me to continue.

hope in the glory of the soul and the body after death guides me. I also know that even if I die during my work I will live again in Christ. The third motivation is the brothers and sisters with whom I live. I have a brother, Fr. Brice Patrique, an Augustinian father, the Carmelite religious who are with us in the mission and do extraordinary work in the most prudent way. The community of Christian brothers and sisters who are there. We help each other, we speak to each other and we encourage each other. We know that the other priests in the other parishes are fighting for the same cause, that is say to establish justice and peace through reconciliation. This is the motivation that encourages us, spurs us on, and leads me to continue.

R: Your example is alarming, shocking in a certain sense. The world we are going through today is full of fear and terror. You only have to look at what happened in Paris a year ago. You need only look at the attacks. So we ask questions about Islam and Muslims. But you, you are narrating something else to us, you are offering another example: that it is necessary to establish a dialogue. You have explained to me that it is necessary to create a dialogue today with Muslims despite everything that we seen done in the name of Allah. Which is not a cry of death and terror but, rather, one of reconciliation with God. Why is this important for you and why is it important for us?

K: I say to myself: are these people who shout Allah Akbar, as a synonym for death, real Muslims?

R: You still live near to Muslims, you hear them praying and imploring Allah Akbar, and what do you feel when you hear that?

K: For me it is only a community of people who live their lives and their religion and believe in God. I believe that the God they believe in is the same God in whom we believe. The Muslims that I host in my home are people who, for example, when they come to be treated in the hospital say “I don’t have any money today. Treat me, I will bring you what I owe you, I will come back tomorrow to pay you”. They always come back to honour their debts. I see honesty in them but I do not see it in the Jihadists, I do not know if they are real Muslims, I know that they are many Muslims who suffer because these others use their religion and their God to do wrong. What can we do for them – they suffer as we suffer?

There are many people in this country. There are many Muslims who suffer because of this situation, because the community uses their name and their God to do wrong. On the other hand, generalisation provokes rejection/refusal by the community. One should really divide situations in order to find a meaning and truly and justly love each other. The rejection of these people by society is radicalising even more.

R: Your response to all the suffering generated by abuse of the name of God is to respond with love, charity and mercy.

K: Certainly. This is so important and obvious. Many people, I will say this again, resort to radicalisation because they feel rejected. The answer must not be force, as has been the case hitherto, instead love is needed! We must rapidly find a solution for those people that we reject.

R: The figure, the presence, the smile and the words of Pope Francis. What has he given to the country you work in with your religious brothers, with the people who take of other people together with you?

R: The figure, the presence, the smile and the words of Pope Francis. What has he given to the country you work in with your religious brothers, with the people who take of other people together with you?

K: At the present time, we are living in a precarious situation but every country is impatient to receive the Pope; respecting his programme we would like to bring Christians, Muslims and non-Muslims together. There are very many people who are waiting to live a period of reconciliation and peace; there are many people who await his arrival as a sort of blessing. His presence is a symbolic expression of the blessing of God for all men and women who are killed by war and divisions.

R: What does Pope Francis represent for you?

- K. The Pope helps me to focus on what I said previously about my mission: love. Love and love.

R: Fr. Bernard, I have understood why Human Rights Watch decided to give you a prize and I am convinced that this prize is not only for you but also for all those people who take care of others in the name of St. Camillus and also in the name of Jesus who sent you. For us it is a privilege, an honour, a grace and a blessing to have you here with us.

Camillians on Facebook

Camillians on Twitter

Camillians on Instagram