It was not only ‘Cardinal Mondovì’ who at the beginning showed himself ‘loving and affectionate towards Camillus, but also other personages, in particular Cardinal Sans who gave a report to the Pope on what had been decided at the Sacred Congregation [for the approval of the Society, seu Congregationem, of the Ministers of the Sick 18 March of the same year, 1586] and praised and commended a great deal this Institute, which, together with the goodness and charity of the Founder, led the Pope to wish to see him and meet him’.

After learning of this ‘wish’ of the Pope through Monsignor Cassano, the Secretary of the Congregation of Bishops and Regulars, Camillus ‘immediately went to see the Pontiff in the Vatican where, after kissing his feet, told him with words of holy simplicity that he was Camillus, a useless servant, who had unworthily been used by God to begin that Congregation which had been recently been confirmed by His Holiness; thus he had gone to thank him and to place that Congregation for always under the wings of that Holy See. The Pontiff replied that he was very happy to see him and meet him, promising that where this was necessary he would always help them and favour them, willingly accepting the whole of the Congregation under his protection’.

In Vms the ‘protection’ granted by the Supreme Pontiff to ‘the whole of the Congregation’ is not mentioned. It appeared for the first time in the edition of 1615.

The meeting of these two men, directed towards a single – albeit diversified – ideal, increased the stimulus to meet each other even before they had met each other personally, and obtained the effects promised by the wishes of the two protagonists. ‘The Pope’, writes Martindale, ‘looked in silence at that exceptional face’. Sixtus, who undoubtedly understood people, realised that he had in front of him a very strong man, so strong that he had been able to conquer himself’.

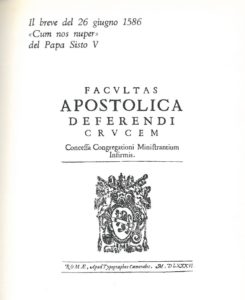

‘In that benevolent answer that was given’, the account goes on, ‘Camillus was strongly moved to ask that he, like all the other members of his Congregation, could wear a cross made of red cloth between the cassock and the cloak, as a distinctive sign of them and the other Clerics Regular’.

The ‘others’ were the Theatines (1524), the Barnabites (1530), the Somascans (1534), and the Jesuits (1524). This distinction – in the nature of a sign – was offered at that time as a convincing reason that was immediately perceivable and useful. But the ‘cross’ was something more for Camillus: it was a ‘sign’ that prius cognitum leads to cognitionem alterius; a ‘sign’ of the charism given to Camillus by the Spirit; a ‘sign’ of the mother-idea, which was indispensable, a symbol and depiction, because ‘as psycho-sociology and cultural anthropology teach, a deep intention cannot be lived for a long time without symbolic-ritual portrayals (that express the image that a man makes of himself in the world) or without the support of a significant community with its typical framework of reference and self-preservation, rooted in the common faith of a group’.

This was a ‘sign’ that had already come to Camillus one August evening four years previously when he ‘one evening in the middle of the Hospital [of St. James] when thinking about these suffering of the poor had the following idea: that these difficulties [the bad service in the hospital] could be remedied in no better way than by creating a Congregation of pious and good men who in making up for every failing of these mercenary servants would have an Institute to help and serve these poor people, not for gain but as volunteers and for love of God; with that charity and lovingness that mothers have with their sick children. He also thought in this first insight that these pious men, so that they could be known in the world as such, could wear a sign of the cross on their clothes…This happened to our father in the year 1582 which was the tenth year of the pontificate of Gregory XIII at the time of the feast day of the Most Holy Assumption of Mary always Virgin, in August’.

CONTINUE READING HERE

Camillians on Facebook

Camillians on Twitter

Camillians on Instagram