The motto for the showing of the Turin Shroud is ‘The Greatest Love’. These are the words of Jesus taken from the Gospel according to St. John (15:13): ‘The greatest love a person can have for his friends is to give his life for them’.

The motto for the showing of the Turin Shroud is ‘The Greatest Love’. These are the words of Jesus taken from the Gospel according to St. John (15:13): ‘The greatest love a person can have for his friends is to give his life for them’.

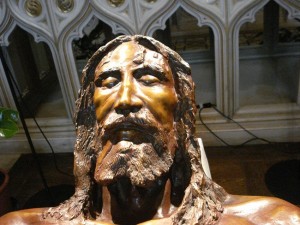

Discovering and living love also means fulfilling one’s deep vocation as a man or a woman, placing oneself at the service of one’s brothers and sisters. It is here that the teaching of Jesus and the message of the Turin shroud meet each other and fuse: the image of the crucified Christ is a sign of suffering and death but also proclaims all the hope that comes form the ‘new fact’ of the Resurrection of the Lord.

The extraordinary showing of the Turin shroud amounts to a pilgrimage that would like to draw believers and non-believers near to the Shroud and to the deep questions about life; and to welcome with especial care and affection the sick who are the direct witnesses of that suffering that the image of the Man of Pain expresses and invokes on the fabric.

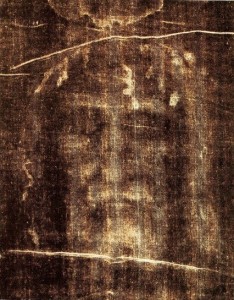

The Turin Shroud is a challenge for our intelligence. It first of all requires of every person, particularly the researcher, that he humbly grasp the profound message it sends to his reason and his life. The mysterious fascination of the Shroud forces questions to be raised about the sacred Linen and the historical life of Jesus.

For the believer, what counts above all is that the Shroud is a mirror of the Gospel. Whoever approaches it is also aware that the Shroud does not hold people’s hearts to itself, but turns them to him, at whose service the Father’s loving providence has put it. For every thoughtful person it is a reason for deep reflection, which can even involve one’s life. The Shroud is thus a truly unique sign that points to Jesus, the true Word of the Father, and invites us to pattern our lives on the life of the One who gave himself for us.

The image of human suffering is reflected in the Shroud. It reminds modern man, often distracted by prosperity and technological achievements, of the tragic situation of his many brothers and sisters, and invites him to question himself about the mystery of suffering in order to explore its causes. The imprint left by the tortured body of the Crucified One, which attests to the tremendous human capacity for causing pain and death to one’s fellow man, stands as an icon of the suffering of the innocent in every age: of the countless tragedies that have marked past history and the dramas that continue to unfold in the world.

The image of human suffering is reflected in the Shroud. It reminds modern man, often distracted by prosperity and technological achievements, of the tragic situation of his many brothers and sisters, and invites him to question himself about the mystery of suffering in order to explore its causes. The imprint left by the tortured body of the Crucified One, which attests to the tremendous human capacity for causing pain and death to one’s fellow man, stands as an icon of the suffering of the innocent in every age: of the countless tragedies that have marked past history and the dramas that continue to unfold in the world.

Before the Shroud, how can we not think of the millions of people who die of hunger, of the horrors committed in the many wars that soak nations in blood, of the brutal exploitation of women and children, of the millions of human beings who live in hardship and humiliation on the edges of great cities, especially in developing countries? How can we not recall with dismay and pity those who do not enjoy basic civil rights, the victims of torture and terrorism, the slaves of criminal organisations? By calling to mind these tragic situations, the Shroud not only spurs us to abandon our selfishness but leads us to discover the mystery of suffering, which, sanctified by Christ’s sacrifice, achieves salvation for all humanity.

The Shroud is also an image of God’s love, as well as of human sin. It invites us to rediscover the ultimate reason for Jesus’ redeeming death. In the incomparable suffering that it documents, the love of the One who “so loved the world that he gave his only Son” (Jn 3:16) is made almost tangible and reveals its astonishing dimensions. In its presence believers can only exclaim in all truth: “Lord, you could not love me more!”, and immediately realize that sin is responsible for that suffering: the sins of every human being.

As it speaks to us of love and sin, the Shroud invites us all to impress upon our spirit the face of God’s love, to remove from it the tremendous reality of sin. Contemplation of that tortured Body helps contemporary man to free himself from the superficiality of the selfishness with which he frequently treats love and sin. Echoing the word of God and centuries of Christian consciousness, the Shroud whispers: believe in God’s love, the greatest treasure given to humanity, and flee from sin, the greatest misfortune in history.

As it speaks to us of love and sin, the Shroud invites us all to impress upon our spirit the face of God’s love, to remove from it the tremendous reality of sin. Contemplation of that tortured Body helps contemporary man to free himself from the superficiality of the selfishness with which he frequently treats love and sin. Echoing the word of God and centuries of Christian consciousness, the Shroud whispers: believe in God’s love, the greatest treasure given to humanity, and flee from sin, the greatest misfortune in history.

The Shroud is also an image of powerlessness: the powerlessness of death, in which the ultimate consequence of the mystery of the Incarnation is revealed. The burial cloth spurs us to measure ourselves against the most troubling aspect of the mystery of the Incarnation, which is also the one that shows with how much truth God truly became man, taking on our condition in all things, except sin. Everyone is shaken by the thought that not even the Son of God withstood the power of death, but we are all moved at the thought that he so shared our human condition as willingly to subject himself to the total powerlessness of the moment when life is spent. It is the experience of Holy Saturday, an important stage on Jesus’ path to Glory, from which a ray of light shines on the sorrow and death of every person. By reminding us of Christ’s victory, faith gives us the certainty that the grave is not the ultimate goal of existence. God calls us to resurrection and immortal life.

The Shroud is an image of silence. There is a tragic silence of incommunicability, which finds its greatest expression in death, and there is the silence of fruitfulness, which belongs to whoever refrains from being heard outwardly in order to delve to the roots of truth and life. The Shroud expresses not only the silence of death but also the courageous and fruitful silence of triumph over the transitory, through total immersion in God’s eternal present. It thus offers a moving confirmation of the fact that the merciful omnipotence of our God is not restrained by any power of evil, but knows instead how to make the very power of evil contribute to good. Our age needs to rediscover the fruitfulness of silence, in order to overcome the dissipation of sounds, images and chatter that too often prevent the voice of God from being heard.

This icon of Christ abandoned in the dramatic and solemn state of death, which for centuries urges us to go to the heart of the mystery of life and death, to discover the great and consoling message it has left us. The Shroud shows us Jesus at the moment of his greatest helplessness and reminds us that in the abasement of that death lies the salvation of the whole world. The Shroud thus becomes an invitation to face every experience, including that of suffering and extreme helplessness, with the attitude of those who believe that God’s merciful love overcomes every poverty, every limitation, every temptation to despair.

This icon of Christ abandoned in the dramatic and solemn state of death, which for centuries urges us to go to the heart of the mystery of life and death, to discover the great and consoling message it has left us. The Shroud shows us Jesus at the moment of his greatest helplessness and reminds us that in the abasement of that death lies the salvation of the whole world. The Shroud thus becomes an invitation to face every experience, including that of suffering and extreme helplessness, with the attitude of those who believe that God’s merciful love overcomes every poverty, every limitation, every temptation to despair.

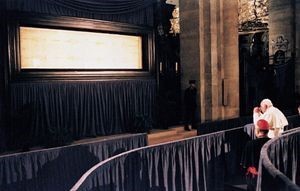

Some observations taken from the address of Pope John Paul II, Turin, 24 May 1998.

Camillians on Facebook

Camillians on Twitter

Camillians on Instagram