‘IT IS NO GOOD LEARNING TO HELP THE SICK IF ONE DOES NOT LEARN TO HELP WITH ONE’S OWN BRAIN AND ONE’S OWN HEART’

International Nurses Day

12 May 2015

The eighty-fifth anniversary of the proclamation of St. Camillus and St. John of God as the patron saints of nurses

The eighty-fifth anniversary of the proclamation of St. Camillus and St. John of God as the patron saints of nurses

Florence Nightingale, the founder of modern nursing, was born on 12 May 1820. The International Council of Nurses (the ICN is a federation of more than 130 national nurses’ associations which represent more than thirteen million nurses in the world) commemorates this date by celebrating throughout the world the International Nurses Day.

In the 1960s in Italy the Consociation (CAIOSS), the nurses’ associations and some provincial colleges, celebrated 12 May. The declared intention of the leaders of these bodies was to call the attention of public opinion to the values of which the nursing profession is a bearer: ‘a profession that finds its most original and authentic meaning in service to man’.

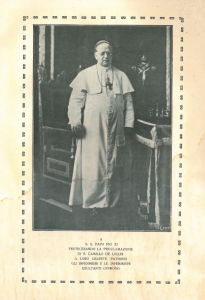

This year will also witness the eighty-fifth anniversary of the proclamation of St. Camilus and St. John of God as the patron saints of nurses (Pope Pius XI, Brief Ad perpetuam rei memoriam, 1930).

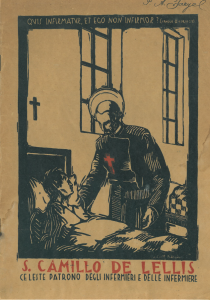

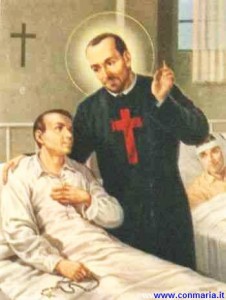

St. Camillus had a valuable message for contemporary nurses and it can be a source of inspiration for them. Camillus was first of all and above all else a nurse. But he was also a model nurse and always had in mind revolutionising the method by which the sick were cared for so as to improve their condition.

In reading about Camillus’ approach to the sick one cannot but ask oneself in wonderment whether Camillus was a product of four hundred years ago or whether, instead, he is not a figure of modern times. His vision is more in harmony with modern nursing schools than with that of those who provided service in the terrible hospital conditions of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Nowadays in nursing science a great deal of emphasis is placed on the concept of global and holistic care.

In the view of Rene Leriche, pain is ‘the result of conflict between stimuli and the totality of the person’. This conflict, this pain, can have effects in any dimension of the personality: the physical, the emotional, the intellectual and the spiritual. A pain of a physical nature does not have effects only on the body but also tends to invade all the parts of our personality because one cannot create compartments that separate the various dimensions from each other. Each dimension is a part without which the whole is incomplete. For that matter, this part cannot function without coordination with the others. All of this is clear to us today but at the end of the sixteenth century this idea was the engine of revolutionary action.

Camillus knew how to distinguish between ‘the illness’ and ‘being ill’. An illness is a structural disturbance of an organ or tissue which, as a result, causes the signs of bad health. Being ill, on the other hand, is the experience that the sick person has of his or her bad health. Being ill has an effect on every dimension of the person just as every dimension of the being of a person bears upon the organ that is sick. One can say that the meaning of the various kinds of suffering and pain in sick people who suffer the same malady lies in the fact that ‘being ill’ is distinct and individual. Thus it is that faced with a patient of the same ward, with the same age and sex, the same number of children and the same illness of the person that has gone before, we cannot allow ourselves to treat him or her in the same way because we can be sure that the effect of the illness on him or her is not the same. There is no group in the hospital world that is as aware of this as men and women nurses are. Camillus, that giant of charity, can be a source of inspiration for every care professional!

Camillus knew how to distinguish between ‘the illness’ and ‘being ill’. An illness is a structural disturbance of an organ or tissue which, as a result, causes the signs of bad health. Being ill, on the other hand, is the experience that the sick person has of his or her bad health. Being ill has an effect on every dimension of the person just as every dimension of the being of a person bears upon the organ that is sick. One can say that the meaning of the various kinds of suffering and pain in sick people who suffer the same malady lies in the fact that ‘being ill’ is distinct and individual. Thus it is that faced with a patient of the same ward, with the same age and sex, the same number of children and the same illness of the person that has gone before, we cannot allow ourselves to treat him or her in the same way because we can be sure that the effect of the illness on him or her is not the same. There is no group in the hospital world that is as aware of this as men and women nurses are. Camillus, that giant of charity, can be a source of inspiration for every care professional!

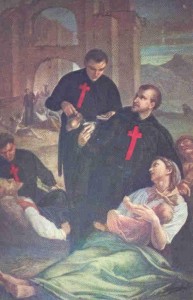

It is always very effective to reflect upon the contribution that St. John of God and St. Camillus de Lellis made to the progress of society in that field of service in which they invested their energies. Holiness, indeed, is not extraneous to true human progress: in truth, holiness is the achievement of full humanity

With great wisdom and prophecy Pope Benedict XVI pointed this out to the young people who has gathered together in Marienfeld (Cologne) on the occasion of the World Youth Day: ‘Through these individuals [saints and blesseds] he wanted to show us how to be Christian: how to live life as it should be lived – according to God’s way. The saints and the blesseds did not doggedly seek their own happiness, but simply wanted to give themselves, because the light of Christ had shone upon them. They show us the way to attain happiness, they show us how to be truly human. Through all the ups and downs of history, they were the true reformers who constantly rescued it from plunging into the valley of darkness; it was they who constantly shed upon it the light that was needed to make sense – even in the midst of suffering – of God’s words spoken at the end of the work of creation: “It is very good”’. A life lived in a holy way is the shuttlecock of great changes that allow a retrieval of the original design of God regarding His creation and His creatures.

This is particularly true of Camillus de Lellis whose role and relevance in the field of care has been increasingly valued and appreciated. The definition of being the ‘founder of a new school of charity’ goes well beyond spiritual boundaries and refers to the progress that he promoted in the health-care field through emphasis on man as a unique and indivisible being and the retrieval of his deepest dignity which was not injured by external conditions of illness or income.

It is advisable, therefore, to think anew about the innovative elements in the figure and the work of Camillus in order to praise his contribution to the human sciences but above all else in order to adopt him as a model for behaviour towards, and care for, the sick and the poor.

A Little History

A recognition of the exemplary character of St. Camillus de Lellis and St. John of God in their work of dedication and service to the sick which meant that they were held up as a model and made the patron saints of health-care workers took place in 1930 during the papacy of Pope Pius XI.

A recognition of the exemplary character of St. Camillus de Lellis and St. John of God in their work of dedication and service to the sick which meant that they were held up as a model and made the patron saints of health-care workers took place in 1930 during the papacy of Pope Pius XI.

Browsing through the Acta Consultae Generalis, a series of documents to be found in the general archives of the Order and evidence on all the decisions taken by the General Consulta since the time of Camillus until today, it is possible to go back over the itinerary that was followed that led up to the declaration that Camillus was the ‘patron saint of nurses’. The process began in the middle of 1930 and ended after a few months. Indeed, on 14 June 1930 Fr. Germano Curti, the Superior General, proposed to the members of the General Consulta that a request should be sent to the Holy See for St. Camillus and St. John of God – who had already been declared the patron saints of hospitals and the sick – to be proclaimed the patron saints of nurses. The formal act of this request was made on 14 July 1930 on the occasion of the liturgical feast day of St. Camillus when the Father General sent a letter to the Secretary of the Sacred Congregation for Rites, Msgr. Alfonso Carinci. In this correspondence Fr. Curti perorated the cause of the proclamation of St. Camillus and St. John of God as the patron saints of nurses.

A few days later, on 26 July, notice was given of the outcome of the audience that had been granted to Cardinal Camillo Laurenti, the Prefect of the Sacred Congregation for Rites, by the Holy Father concerning the request that had been made by the Order. On 23 July Pius XI agreed to the request of the General Consulta and proclaimed St. Camillus de Lellis and St. John of God the patron saints of nurses.

This title was officialised on 11 September 1930 by the pontifical Brief of Pius XI of 28 August 1930, Ad perpetuam rei memoriam.

The Contribution of St. Camillus de Lellis to the Development of Care as a Discipline

In order to emphasise the contribution of St. Camillus to the development of what would become an autonomous discipline, I would like to refer to a paper by Marina Negri.

Formation

St. Camillus upheld the need for formation to create Ministers of the Sick, a formation on the front of pastoral care but also a ‘technical’ formation. St. Camillus said: ‘Being Ministers of the Sick cannot be improvised – they have to be trained!’. To this end he gave talks to novices and to the brothers and fathers. But he also organised what today  we would call ‘drill lessons’. He gathered together the novices, put a table in the middle of the room, put on it a mattress and sheets and asked them to make the bed, perhaps with a brother who pretended to be a sick man lying down a bed. He suggested things, corrected and exhorted. Or he organised today what we would call ‘role playing’: he acted out the presence of a person near to death and exhorted one of those who were present to comfort him, warning him about uttering general moralistic words.This was, therefore, a 360 degree formation.

we would call ‘drill lessons’. He gathered together the novices, put a table in the middle of the room, put on it a mattress and sheets and asked them to make the bed, perhaps with a brother who pretended to be a sick man lying down a bed. He suggested things, corrected and exhorted. Or he organised today what we would call ‘role playing’: he acted out the presence of a person near to death and exhorted one of those who were present to comfort him, warning him about uttering general moralistic words.This was, therefore, a 360 degree formation.

The Specialist Technical Aspect

The ‘Rules to Serve the Sick Well’ which were written by St. Camillus for the use of his religious brothers refer to meeting those needs that today we would define as ‘the needs of nursing care’ (helping a person to eat, positioning them well, fostering their rest, providing for physical needs connected with evacuation, etc.). These recommendations are the point of departure for the application of the current theory of nursing.

St. Camillus not only identified needs, he also invented techniques. For example, he invented techniques of hygiene for the oral cavity, care that was as simple as it was important for those who were unable to provide it to themselves. In St. Camillus this was ‘charity that was as particularly held dear as it was unusual’ and had never been seen before. St. Camillus invented making an ‘occupied bed’, that is to say making a bed when the person in it could not get up or be raised up, and suggested particular methods that made this technique possible. He designed and produced special supports, the mobile urinal and the commode, so that his patients were not forced to go to ‘lavatories that are dirty, smell and also covered in mud’.

A New Method

The rule that was most widespread at the time of Camillus laid down that when a patient was admitted to hospital he or she had to confess and take holy communion. In contrary fashion, St. Camillus recommended that the sick person be received, with comfort being provided through a washing of his or her feet, a change of his or her underwear, and the preparation of a clean and warmed-up bed. St. Camillus also invented the nursing sheet given that he invited his religious to ask questions of the newly admitted patients, about the nature of their maladies and what their symptoms were. Today this is called ‘collecting data’. Then as today, these data were used to plan personalised care.

A characteristic of nursing care is its continuity for twenty-four hours in the day through the exchange of information between groups of nurses as they replace each other. St. Camillus invented the ‘handover’, that is to say the handing over of information about the situation of a patient which was directed towards achieving better nursing care. St. Camillus recommended those who began their roster to act ‘according to the information handed over that they find on the desk written by their religious brothers acting  as nurses of the body’.He exhorted everyone to make observations and write them down in this exchange of information so that there would be records of these notes connected with care, thereby avoiding them being forgotten.

as nurses of the body’.He exhorted everyone to make observations and write them down in this exchange of information so that there would be records of these notes connected with care, thereby avoiding them being forgotten.

Organisation

Camillus improved care through his organisation of things. This organisation was based on the division of responsibilities which were given to various members of the care group, in which a figure responsible for coordination was identified.

With Camillus there began to emerge the concept of team work where the team was made up of medical doctors and nurses. This team work was achieved through a constant exchange of information in a linear sequence directed towards achieving the ‘best care for the sick’.

Conclusions

From these brief elements one can deduce that St. Camillus, quite rightly, can be seen as the founder of nursing care from both a technical and scientific point of view and as a discipline. It is certainly true that he did not found a profession: he founded a religious Order. However, he contributed in a determining fashion to defining the contents of nursing care and its implementation. His teaching, which was handed over in the activities of daily life, has remained unchanged until today. And to such an extent that sentences from Florence Nightingale herself, who is seen as the founder of nursing care, seem to be an echo of the profound spirituality of St. Camillus, a testimony of the fact that holiness is deep immersion in the riches of humanity. ‘I have come to the belief that it no use learning to care for the sick if one does not learn to care with one’s own brain and with one’s own heart. Thus if we have a religiosity that is not truly felt, hospital life will become a set of manual actions performed out of habit that will make arid both our minds and our hearts’. Florence Nightingale wrote these words in her ‘Letters to Nurses’. St. Camillus could have written them – in his outlook the heart characterises the style of nursing care. Camillus, Florence and anybody else who care about the wellbeing of people who suffer cannot but draw inspiration from awareness of the fact that in the person who is in front of him or her there is something that goes beyond the real and opens up to Mystery.

Br. Luca Perletti

Evolution of the process concerning the proclamation of St. John of God and St. Camillus de Lellis the patron saints of nurses

St. Camillus the nurse by Eugenio Moriani

Breve di Pio XI

Translation of the Brief of Pius XI

Prayer for nurses and those who treat and care for the sick

Lord,

From you, trusting in the early morning,

Grateful in the evening,

I ask light and blessing

What amazement

At the gift of life

Which passes by way of these poor hands of mine.

Into your hands I deliver

Those who have been entrusted to me;

May your gaze steward us and protect us.

Swift be the step,

Meek the look,

Open the heart,

Strong the hands.

To understand,

To heal,

To restore hope.

A Samaritan on a journey,

Ready for meaningful halts,

I bend down to bandage the wounds

Of the body and the spirit.

Meek instrument of your concern,

More attentive to questions than to answers.

A prophet on a journey.

To you Father, for Mary, Mother of hope,

Of compassion and of tenderness,

I raise this prayer.

At the side of the patient

Who is an image of your Son,

Guide my mind, hands and spirit.

With full trust, untiringly!

Amen! Alleluia!

Camillians on Facebook

Camillians on Twitter

Camillians on Instagram