After the proclamation of the year of St. Joseph by Pope Francis interest in the importance of this saint increased in the Church but also, and in particular, in the Order of Camillians, as has already been emphasised by Fr. Ruffini in previous articles.

After the proclamation of the year of St. Joseph by Pope Francis interest in the importance of this saint increased in the Church but also, and in particular, in the Order of Camillians, as has already been emphasised by Fr. Ruffini in previous articles.

The month of March in traditional popular devotion in past centuries was dedicated to St. Joseph given that the solemnity of this saint – after various changes – was established as taking place on the nineteenth day of March. Here I would like to dwell on two places in the city of Milan where Camilians have commemorated St. Joseph with a special religious and artistic presence – the Church of St. Mary of Health and the St. Camillus Sanctuary.

In Milan: St. Mary of Health.

When Gaspare Visconti became the bishop of the city of Milan in 1585, he called to that city Camillus de Lellis and his confreres. In 27 July 1594 the Congregation entered the Ca’ Granda and remained there to help the sick until the year 1630. In Milan they had their headquarters firstly at Santa Maria Podone and then at Santa Croce in San Calimero until 1632 when they purchased a house with an oratory at the eastern gate and more specifically at the canterana di Porta Tosa (today’s Via Durini).

In 1638 they expanded the little church and opened it to worship the next year, calling it the Church of Santa Maria Salus Infirmorum. In 1694 they left the old oratory and began construction of the new Church of St. Mary of Health.

The Church of St. Mary of Health was a project of Giovan Battista Quadrio. The position of the façade off an axis in relation to the street is a rarity in Milan. It is convex in the central part and this gives the church the nickname of ‘the little violin’. Inside on each side there are two chapels. On the right the first is dedicated to the Queen of the Rosary; the second is dedicated to the Crucified Christ. On the left side the first chapel is dedicated to Camillus de Lellis and the second is dedicated to the ‘transit’ (that is to say the dying moments) of St. Joseph.

The Church of St. Mary of Health (or of the Crucifers) is one of the few examples in Milan of a church with an elliptical nave and a convex façade. It was built according to the plan of Giovan Battista Quadrio in collaboration with Carlo Federico Pietrasanta. It has a single nave but this has four lateral chapels. Built at the end of the seventeenth century and the first two decades of the eighteenth century, the church was dedicated – as its ‘title’ indicates – to the Blessed Virgin Mary. The high altar was built in the year 1731 and is made out of black marble from Varenna and red marble from France. At its centre there is an oil painting attributed to Cesare Magni – a pupil of Cesare da Sesto – and it depicts Our Lady of Divine Putto or Our Lady of Health. It probably came from the old church that the present one replaced. It is a partial copy of a work by Raphael. In 1724 the marble balustrade was added and in 1726 the altarpiece, also in marble, was put in place.

The façade was only begun in the second decade of the eighteenth century but it was never completed and still today is made up of simple exposed bricks.

The completion of the church went on for the whole of the first part of the eighteenth century, with the altar in multi-coloured marble and accessory parts (1713-1726), the frescoing of the vault by Pietro Maggi (1717), and the completion of the side chapels, amongst which the one dedicated to St. Camillus de Lellis which is decorated with multi-coloured marble and gilt bronzes.

The decoration of the chapel dedicated to St. Joseph, the first chapel on the right, was in fact only completed in 1760.

The Church of St. Mary of Health is characterised by the presence of a single elliptic nave which is elliptical, has two chapels in its two sides and a large presbytery. The elliptical character of the inside is pre-announced by the outside of the markedly convex façade which, as has been observed, was never completed. It is divided into two sections by a marked cornice. At the top there is a large curvilinear pediment. On both the lower and the upper sections of the nave there are frames in the baroque style, evidently intended to have plaques and bas-reliefs. However, they have all remained empty, like the two niches on either side of the entrance door. A pulpit is present on each side of the nave on the wall.

The vault takes the shape of a bezel elliptical form. At its centre inside a mixtilinear painting in gilded stucco there is a painting of the Assumed Mary, the work of Pietro Maggi of 1717.

The four side chapels have marble altars and elegant balustrades. The first on the left-hand chapel (when entering the church) is dedicated to Camillus de Lellis and was finished in 1742 (the year of his beatification) when it was given a valuable altar in marbles and gilt bronzes on which there is a painting of the saint.

The second chapel on the left is dedicated to St. Joseph and the decoration of this chapel was only completed in 1760.

The second chapel on the left is dedicated to St. Joseph and the decoration of this chapel was only completed in 1760.

When in 1781 Joseph II ordered the suppression of all religious Orders, the Ministers of the Sick to begin with were saved but with the second arrival of Napoleon they were also dissolved – in the year 1810. The Camillians returned to Milan in 1896 and built a new sanctuary which they inaugurated in 1912 Via Boscovich giving it the name of Camillus de Lellis.

Between 1966 and 1985 the Church of St. Mary of Health experienced a period of degradation, and at times was closed because it was not safe. It was restored on a large scale and reopened to the public in 1996.

Joseph in the St. Camillus Sanctuary

In this sanctuary there stands out the small Chapel of St. Joseph at the beginning of the right-side stairway that leads to the sacellum of Our Lady of Health. The marble altar was made in 1935 by Remuzzi according to the plan of Annibale Pagnone. The oil painting depicting St. Joseph, venerated as the patron saint of the dying helped by Jesus and Mary, is by Prof. Pietro Verzetti of the Academy of Brera.

On the walls decorated with pink marble are four mosaic panels which happily contain, against a canary yellow background, biblical symbols praising the greatness of St. Joseph.

On the left of the altar there is a fine palm tree with dates with the caption: ‘the just will blossom like the palm’. On the right of the altar there is a giant cedar tree with the caption: ‘he will rise up like the cedar of the Lebanon’ (psalm 91).

like the cedar of the Lebanon’ (psalm 91).

In front of these, in another two mirrors, symbols of the dynasty of David in mosaic form are to be found: a crown above a sceptre with the words ‘You placed on your head a crown of precious stones (psalm 20), as well as the work tools that characterised the hard-working life of the carpenter of Nazareth: a saw, a hammer and a plane, amongst which the traditional lily blooms. Underneath we read: ‘The work of his hands will bloom – with the lily – for eternity’ (from the liturgy). The Sgorlon Company did these mosaics based on the drawings by Elena Mazzari of Milan. On the coloured windows there is a lily with the phrase ‘Ite ad Ioseph’ (‘Go to Joseph’).

Continuing our visit to the inside of the sanctuary we find other references to St. Joseph, which are never detached from those to St. Mary, as we can observe in the stained-glass window under the central pinnacle of the altar to the Blessed Virgin of the Carmel. The celestial face of St. Joseph has a lily in his hand which is a symbol of God choosing that he should marry St. Mary.

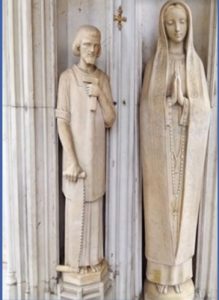

On the outside of the building in the pronaos we find another four statues that decorate the entrance and here we encounter St. Joseph (the carpenter), Our Lady of Fatima, and together with them the apostles St. Peter and St. Paul (all of these statues are 1.15 metres high).

Some observations:

It is highly surprising that the painting in the Church of Our Lady of Health of the eighteenth century in Via Durini in Milano was a ‘novelty’ for the Order of Camillians. Indeed, it does not correspond to the Salus infirmorum painting to be found in the Church of St. Mary Magdalene in Rome. From the chronicles of the time, in fact, one reads that to every Camillian community of the seventeenth century a copy of the painting by Fr. Cesare Simonio was sent. It seems impossible that such a copy did not reach Milan where there was a large community of Camillian religious that had been founded by St. Camillus.

It is highly surprising that the painting in the Church of Our Lady of Health of the eighteenth century in Via Durini in Milano was a ‘novelty’ for the Order of Camillians. Indeed, it does not correspond to the Salus infirmorum painting to be found in the Church of St. Mary Magdalene in Rome. From the chronicles of the time, in fact, one reads that to every Camillian community of the seventeenth century a copy of the painting by Fr. Cesare Simonio was sent. It seems impossible that such a copy did not reach Milan where there was a large community of Camillian religious that had been founded by St. Camillus.

As regards the two paintings of St. Joseph described above, we can observe that the subject of his last moments and death is not present in any of the gospels or in other canonical references of the New Testament. In fact, the episode is to found in the accounts of certain apocryphal writings, for example in the ‘History of Joseph the Carpenter’ in which it is stated that: ‘This is the account of the passage of our holy father Joseph the carpenter, the father of Christ according to the flesh, who lived for one hundred and eleven years. Our Saviour related to the apostles the whole of his biography on the Mount of Olives. The apostles themselves wrote these words and placed them in the library of Jerusalem…Everything that I have told you is summed up in the following: the strong cannot be saved by their strength, nor can anyone save themselves by their great wealth (Jer 9:22-23). Listen now, that I will tell you the story of my father Joseph, the old carpenter. May he be blessed!’

Together with what can be taken from the artistic notes on the presence of St. Joseph, we cannot omit the meaning of what is expressed. What is clear, first of all, is the devotion to St. Joseph as the patron saint of the dying, a ministry that was felt deeply as early as St. Camillus and handed down over subsequent centuries (the eighteenth to the twentieth) with special celebrations (preaching and prayers on Wednesdays, various triduums with the showing of the Most Holy Sacrament, the month of St. Joseph, prayers for the dying and during the last moments of a confrere).

We cannot fail to mention the virtues of St. Joseph: ‘spouse of the Blessed Virgin Mary’, ‘righteous man’, ‘faithful’, ‘worker’, ‘silent’…

At the side of Joseph there is always Mary; at the side of Mary there is always Joseph: these are two coordinates that have become a liturgical praxis for Camillian religious. A praxis that should not be forgotten but, rather, put into practice for the good of the dying in performing the angelic ministry at the side of the sick who are leaving this world to enter the glorious life of Christ and Mary, helped by the sacred comfort of our Patriarch Joseph.

A simple prayer to the Holy Family

(for the dying)

Jesus, Joseph and Mary.

I give you my heart and my soul.

Jesus, Joseph and Mary, help me in my last few moments.

Jesus, Joseph and May, may my soul expire in peace!

Camillians on Facebook

Camillians on Twitter

Camillians on Instagram