Father Rosario Messina

In his Bull of Indiction for the Holy Year Pope Francis writes in n. 15: ‘It is my burning desire that, during this Jubilee, the Christian people may reflect on the corporal and spiritual works of mercy’. Specifically to respond to this valuable recommendation, I will suggest fourteen reflections, one every week, as many as the number of works of mercy. ‘It will be a way’, the Pope goes on, ‘to reawaken our conscience, too often grown dull in the face of poverty. And let us enter more deeply into the heart of the Gospel where the poor have a special experience of God’s mercy’.

In his Bull of Indiction for the Holy Year Pope Francis writes in n. 15: ‘It is my burning desire that, during this Jubilee, the Christian people may reflect on the corporal and spiritual works of mercy’. Specifically to respond to this valuable recommendation, I will suggest fourteen reflections, one every week, as many as the number of works of mercy. ‘It will be a way’, the Pope goes on, ‘to reawaken our conscience, too often grown dull in the face of poverty. And let us enter more deeply into the heart of the Gospel where the poor have a special experience of God’s mercy’.

Let us attempt first of all to explain the terms involved. WORKS. In the view of St. James, man is justified and thus saved on the basis of works and not only on the basis of faith: ‘what good is it for people to say that they have faith if their actions do not prove it? Can that faith save them? Suppose there are brothers and sisters who need clothes and don’t have enough to eat. What good is there in saying to them, “God bless you! Keep warm an eat well!”, if you don’t give them the necessities of life? So it is with faith: if it is alone and includes no actions, then it is dead’ (Jm 2:14-18). A living faith, therefore, necessarily requires industrious charity, which thereby becomes the distinctive mark of Christians: ‘If you have love for one another, then everyone will know that you are my disciples’ (Jn 13:35). Heaven, therefore, is only for those who have loved: ‘Not everyone who calls me “Lord, Lord” will enter the Kingdom of Heaven, but only those who do what my Father in heaven wants them to do’ (Mt 7:21).

MERCY. In Italian the result of a fusion of ‘miseria’ (‘misery’) and ‘cuore’ (‘heart’), this words means ‘a special power of God that prevails over the sin and the unfaithfulness of His people’. God is merciful because He is deeply concerned about the misery of man, above all when man suffers. Jesus, the incarnation of the face of the Father, revealed this merciful heart to us, above all in the parable of the prodigal son (Lk 15:11ff). He taught us that man does not only receive and experience the mercy of God – he is also called to ‘use mercy’ towards others: ‘Be merciful just as your Father is merciful’ (Lk 6:36). ‘For God will not show mercy when he judges the person who has not been merciful’ (Jm 2:13). ‘Happy are those who are merciful to others, God will be merciful to them’ (Mt 5:7).

CORPORAL WORKS AND SPIRITUAL WORKS. ‘The glory of God is living man’ (St. Ireneaus). Man is not only his body and not only his spirit: he is incarnated spirit. His needs are many and different. Often the most important are hidden and invisible. Jesus passed by doing good to everyone, healing the sores of the body and assuaging the wounds of the spirit. Healthy philosophy and psychology also teach us that from visible things it is easier to perceive and sense invisible realities.

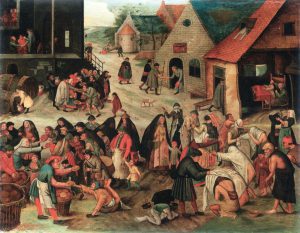

The Ecumenical Second Vatican Council even expanded the vast horizon of works of charity compared to the fourteen that had suggested by the Fathers of the Church and indicated such a vast gamut of situations and needs of man as to constitute a reading with a modern approach of the ancient but always new needs of man. ‘Charitable activities’, we read in Apostolicam Actuositatem, ‘can and should reach out to all persons and all needs. Wherever there are people in need of food and drink, clothing, housing, medicine, employment, education; wherever men lack the facilities necessary for living a truly human life or are afflicted with serious distress or illness or suffer exile or imprisonment, there Christian charity should seek them out and find them, console them with great solicitude, and help them with appropriate relief’.

Lastly, just how important it was for the Christians of the early centuries to achieve consistency and harmony between their faith and their lives, between the spirit and the body, emerges from a passage in an immensely powerful homily of St. John Chrysostom: ‘You want to honour the body of Christ? Do not allow it to be the object of contempt in your members, that is to say the poor, without clothes to cover themselves. Do not honour it here in church with fabrics of silk while outside you neglect it when it suffers from cold and nakedness. He who said ‘this is my body’ also said ‘you saw me hungry and you did not give me anything to eat and every time that you did not do these things to one of the least of these, you did not do it to me’. The body of Christ on the altar does not need cloaks but pure souls, while that which is outside has a great deal of care. Let us learn therefore to think about and honour Christ as he wants’ (homily in Math. Evang., 50).

I would like to end this brief introduction with the words of the Blessed John Paul II who saw a Good Samaritan as ‘everyone who stops beside the suffering of another person, who has compassion for all suffering, who is moved by the misfortune of seeing people weep or die, who knows how to put his heart in every action of goodness and tenderness’ (cf. Salvifici Doloris, 28).

Camillians on Facebook

Camillians on Twitter

Camillians on Instagram